The Breaking Apart of Obamacare

President Donald Trump and the Republicans have no choice about replacing the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA), as the law is generally recognized to be failing. But how to replace this giant law that has affected every part of American society is a matter of urgent and ongoing debate.

The act, also known as Obamacare, is large: It is 2,700 pages long, has generated tens of thousands of pages of regulations, and created more than 100 new boards, commissions, and bureaucracies. ACA is also ambitious. It has been called the largest expansion of American government since the 1960s.

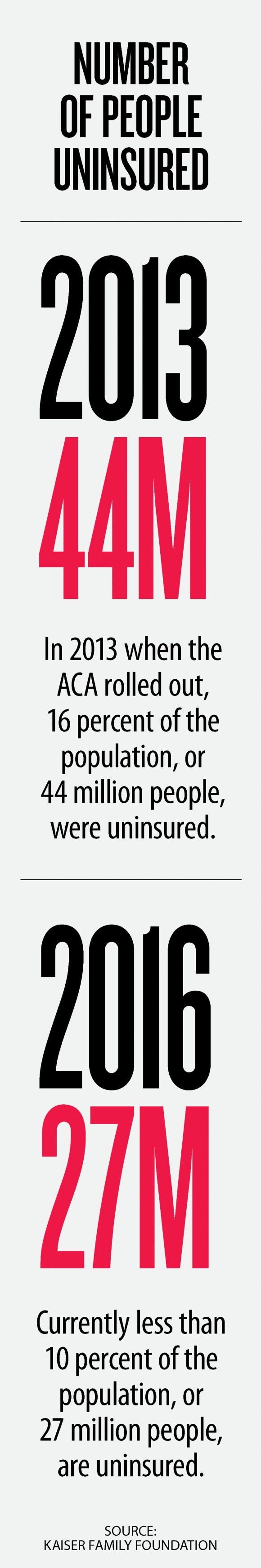

According to the Obamacare Facts website, the ACA was drafted to respond to a health care crisis: a growing number of uninsured Americans; steadily increasing health care costs, and concurrently, rising personal debt and bankruptcy due to those costs; and a burgeoning national debt and deficit. Meanwhile, profits for health care corporations increased.

The act aimed to increase the number of insured and improve the quality of insurance coverage, while “bending the cost curve down,” relieving the pressure on individual, state, and federal budgets. It pursues these goals by shifting power over insurance from individuals, businesses, and states to the federal government.

The ACA’s features include the following: defining the “minimum essential coverage” that all health insurance plans had to offer, which included paying for preventive care; requiring everyone to be covered with health insurance—the individual mandate—or else pay a fine; preventing individuals with pre-existing conditions from being denied insurance; allowing parents to keep children aged 26 and younger on their insurance; and charging women and men the same amount for comparable insurance.

The act set up state-level health care exchanges on which individuals could shop for health insurance and receive a subsidy if they made less than 400 percent of the federal poverty level. It also expanded Medicaid to insure more of the poor and made some reforms to Medicare, which insures the aged.

While the problems with Obamacare have been most evident in the state-run exchanges, difficulties have also emerged in employer-provided insurance, Medicaid, and Medicare.

The Death Spiral

As of March 2016, the Obama administration claimed the ACA had insured around 11 million through the state exchanges and another 11 million through Medicaid.

Twenty-three states set up exchanges under the ACA, while the other 27 refused to take part, leaving the federal government to run exchanges for those states. Of the 23 state-run exchanges, 16 have closed. They were the victims of a failure by the law’s drafters to understand the motivations of the average consumer.

For young, healthy people, the ACA offers a bad deal. The required insurance is comprehensive, covering everything from mammograms to massage therapy. But it is also identical regardless of sex or age. For instance, an elderly couple or a young, single person with no intention of starting a family would both have to pay for coverage of pregnancy and birth control. Reducing premium costs by narrowing the menu of benefits is not possible.

For individuals who might, if allowed to do so, opt for only catastrophic health insurance, the ACA policies have been overly expensive. The penalties for not buying insurance, set for 2017 at $695 or two percent of annual income, have been much cheaper than policy premiums. And health insurance could still be purchased after a serious health problem arose, so there was an incentive to try to game the system. The young and healthy have tended not to buy.

But the structure of Obamacare depended on the young and healthy paying high premiums that would subsidize the old and the sick. The insurance companies were prevented from charging those with pre-existing conditions more and could only charge the elderly at most three times what they charged others. Those over 65, though, consume a disproportionate amount of health care dollars spent.

At the same time, with free preventative and other care, people who purchased the ACA policies tended to use the benefits available to them, racking up high expenses for the insurance companies.

Complicating the situation, a system set up by the ACA to offset losses by insurance companies, called risk corridors, failed to work as planned. The ACA planners realized that some insurers might get stuck with older, sicker populations than others. So to even out the risk, the insurers who attracted healthier consumers would pay into a fund, and those insurers with sicker populations would receive subsidies.

The result has often been that insurance companies that were already losing heavily in the exchanges were then asked to pay multimillion dollar amounts into the risk corridor funds. In total, insurers have requested $2.87 billion from the risk corridor funds, but only received $360 million. Some of these companies are now suing the federal government.

Some of the biggest health insurances companies—Aetna, UnitedHealthCare, and Humana—have pulled out of most of the exchanges, leaving many states with only a single insurer.

The Obama administration announced that, on average, health insurance premiums offered through the ACA will increase by 25 percent in 2017, while the number of insurance plans available will decrease by one-third. This dramatic rise in price and narrowing of options has set the stage for even more failure, as more young and healthy people choose not to pay such high premiums, making the exchanges even more financially unstable and possibly leading to what actuaries call a death spiral.

Insurance From Employers

Nearly half of Americans (155 million) still get their insurance through their employers.

According to a three-year, longitudinal study by the National Federation of Independent Business conducted from 2013–2015, small businesses did not experience a drop in health insurance costs due to the implementation of Obamacare. Sixty-three percent experienced price increases from mid-2014 to mid-2015. Small businesses also struggled with the administrative costs of the complicated law.

The small businesses absorbed the increasing costs of health insurance by seeking to increase productivity, lowering profits, increasing prices, reducing business investment, increasing the employee’s costs for health insurance, and freezing employee wages.

Businesses increase the employee’s costs by charging higher deductibles or co-pays and by narrowing the network of providers.

When Obamacare was first implemented in 2013, a report by the financial research firm S&P Capital IQ predicted that by 2020, 90 percent of employees who got their health insurance from companies would be shifted to government exchanges, which would allow employers to avoid much of the higher costs imposed by the ACA. The estimated savings for the years 2016–2025 for the largest companies were dramatic: $700 billion, or 4 percent of the total value of those companies, according to the report.

With the collapse of the exchanges and the imminent repeal and replacement of the ACA, this hasn’t started happening.

Large companies are taking other measures to cut the steeper costs imposed by the ACA, including no longer offering insurance to spouses and raising the costs of co-pays and deductibles. Employers are also turning to consumer-driven health plans that offer the employee a savings account for routine medical expenses paired with a catastrophic health insurance plan.

Medicaid and Medicare

Both Medicare and Medicaid have been adversely affected by Obamacare.

Medicaid is a troubled program. According to several studies, health outcomes are often better for the uninsured than for those on Medicaid. Part of the problem is that an increasing number of doctors are refusing to accept Medicaid, whose reimbursement rates are low. This means that specialists may not be available through Medicaid, even though on paper the program covers their services. According to a Health and Human Services study released in 2014, half of the doctors listed as Medicaid providers could not offer appointments to enrollees.

The ACA’s expansion of Medicaid has caused the disabled insured by it to have more difficulty in receiving care. Again, this is a problem of incentives.

Obamacare provides nearly twice the funding for states to sign up non-disabled adults than it provides for the care of the disabled who are on Medicaid. According to Chris Jacobs of the Juniper Research Group, this has contributed to over 500,000 developmentally disabled patients being put on waiting lists.

According to the Congressional Budget Office, Obamacare would cut $716 billion from Medicare over 10 years’ time. According to the Obamacare Facts website, these cuts are not really cuts, but rather savings realized from cutting overpayments to hospitals and instances of fraud and abuse. These savings are reinvested, according to the website, in fully funding prescription drugs for Medicare recipients and in other ways in Obamacare and Medicare.

The Heritage Foundation cites the 2012 Medicare trustees report to conclude that the ACA’s cuts to Medicare “will cause an estimated 15 percent of hospitals, skilled nursing facilities, and home health agencies to operate at a loss by 2019, 25 percent to operate at a loss in 2030, and 40 percent by 2050.”

Bitter Politics

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) was shaped, in part, by the intense partisanship it aroused. That partisanship may in turn limit the possibilities for replacing the law.

According to Thomas Mann, a senior fellow at the liberal Brookings Institute, “Before Obama was inaugurated, Republican congressional leaders made a strategic calculation that the best route to reclaim the majority in Congress was to unify in opposition to all of Obama’s major initiatives.”

Norm Ornstein, a resident scholar at the conservative American Enterprise Institute, recounted in an article for The Atlantic how Senate Republican leader Mitch McConnell shut down negotiations by Republican senators over health care reform.

Ornstein reports that McConnell said Republican unity in opposition was necessary, “Because if the proponents of the bill were able to say it was bipartisan, it tended to convey to the public that this is OK.” According to Ornstein, McConnell’s stance was hardball politics.

James Capretta, a resident fellow at the American Enterprise Institute (AEI), wrote in an article for National Review that the Republicans could not cooperate in passing ACA because the Obama administration had insisted “on parameters for the legislation that the GOP could never agree to (such as large tax increases on households to pay for much of the added spending).”

In the end, the ACA was passed in both the House and the Senate without a single Republican vote.

After the law’s passage, the Republicans complained that major social programs, like Social Security or Medicare, had previously only been passed with bipartisan support.

The Republicans also cried foul at procedural gimmickry used by the Democrats to get ACA passed in the face of unified opposition. At the time, Democratic Rep. Alcee Hastings of the House Rules Committee said, “We’re making up the rules as we go along.”

And the Republicans complained that the case made for Obamacare was dishonest. President Barack Obama repeatedly promised that families would see their premiums drop by $2,500, that if one liked one’s doctor one would be able to keep one’s doctor, and that if one liked one’s plan one would be able to keep one’s plan.

In a 2014 interview with Huffington Post, former House Financial Services Committee Chairman Barney Frank (D-Mass.) said the president “should never have said as much as he did, that if you like your current health care plan, you can keep it. That wasn’t true. And you shouldn’t lie to people.”

In 2014, videos surfaced of MIT professor Jonathan Gruber, who had been described as an architect of Obamacare, saying that lies were needed to pass the bill.

In one passage, Gruber said, “Lack of transparency is a huge political advantage. And basically, call it the stupidity of the American voter, or whatever, but basically that was really, really critical to get the thing to pass.”

Ron Fournier, a journalist writing in The Atlantic and a supporter of the ACA, concluded after seeing the Gruber videos, “Obamacare was built and sold on a foundation of lies.”

Frank said, “Any smart political adviser would have said [to Obama], ‘Don’t lie to people, because you’re gonna get caught up in it, and it’s gonna have this tsunami that you now have.’”

The lack of bipartisanship, and the questions raised about how the ACA was sold to voters and passed Congress, indeed led to a political tsunami.

In the 2010 midterm elections, the Republicans gained control of the House of Representatives, with anger over the ACA playing a significant role in their victory. In 2014, Republicans gained control of the Senate, again running against Obamacare. In 2016, Donald Trump ran for president on a platform that included repealing and replacing the act.

The ACA has never been popular. According to the stat-analysis website 538, from the time of its enactment to today the ACA has never been above the mid-40s in popularity.

Because of the gimmickry needed to pass Obamacare, the Democrats ended up with a law even its supporters admit is in need of fixing, but in the polarized climate in Washington, the cooperation needed from the Republicans has in most cases not taken place.

A Republican Alternative

Sen. Chuck Schumer (D-N.Y.) said of the Republicans’ plans for replacing Obamacare, “They don’t know what to do. They’re like the dog that caught the bus.”

While Republicans have offered several different plans, they are giving signs of knowing what they want to do.

Yuval Levin, editor of National Affairs, wrote in an article for National Review that a consensus is forming among Republicans about what a replacement would look like. This approach “combines returning insurance regulation to the states, a federal tax credit for coverage in the individual market, and continuous-coverage protection to cover Americans with preexisting conditions.”

However, the Republicans face at least three stiff challenges in passing a replacement for Obamacare.

First, the status quo is not sustainable. The Republicans can’t delay in acting, and whatever proposal they put forward needs to reassure insurance companies that are ready to abandon the Obamacare exchanges.

Second, some 22 million Americans have gained insurance through the ACA exchanges or Medicaid. Capretta of AEI proposes that Republicans grandfather these in indefinitely. Capretta assumes that over time these individuals will avail themselves of insurance offered by the replacement for the ACA.

Third, Democratic cooperation is needed to replace the ACA with a new program. The Republicans can repeal the ACA by stripping it of funding with a simple majority vote using the legislative mechanism called reconciliation, which applies only to budgetary matters.

To replace the ACA, the Republicans will need to attract eight Democratic votes to overcome the possibility of a filibuster in the Senate. Schumer now has the opportunity to take the hard line stance McConnell took, and has vowed not to cooperate with any Republican plan to replace the ACA.

Trump may have helped make this cooperation more likely by stating three goals for the Republican bill that are significant parts of the ACA: universal coverage, no denial of insurance to those with pre-existing conditions, and insurance for enrollees’ children aged 26 and younger. Only time will tell whether the Republicans adopting these features of Obamacare will soften Democratic opposition.

Within hours of being inaugurated, Trump set the Republican effort for repealing and replacing Obamacare into motion by signing an executive order that empowers the bureaucracy “to the maximum extent permitted by law” to begin rolling back the provisions of Obamacare.